Chances are you have never picked up and read his Aerial Attack Study—an Air Force official document that codified aerial maneuvers for pilots interested in dominating their opponents in air-to-air combat.

You may not be aware of the Energy-Maneuverability (E-M) theory he co-created that essentially gave engineers the ability to quantifiably measure fighter aircraft agility pre- and post-design.

In the Pentagon, he was a Reformer or “Maverick” who fought against the improper use of technology, arguing that people are more valuable than technology. In and outside the Pentagon he preached a simple heuristic for use in complex environments: “People, ideas, and hardware—in that order!”

His name is John Boyd and chances are you just learned something about Boyd you didn’t know. But did Boyd loath Lean?

John R. Boyd was a TOPGUN, a maverick whose most recognized contribution to those interested in surviving and thriving on their own terms was his non-linear learning and adaption process known as the OODA loop.

John Boyd’s Observe-Orient-Decide-Act (OODA) loop—sketched in 1995, 30+ years after his Aerial Attack Study and 25+ years after he developed E-M theory—is the foundation and mindset of Scrum, it inspired the book, The Lean Startup and Steve Blank’s Customer Development Model, and is used by industry leaders in cyber security, Big Data, DevOps, design thinking, healthcare, AI/ML, Human-Machine Teaming, strategy, first response, policing, homeland security, safety, patient safety, team science, marketing, politics, and 3rd through 5th Generation Warfare (social). Anywhere non-linearity exists, you’ll find leaning-forward leaders and high-performing organizations “flying” the OODA loop[1].

So, What does this have to do with Lean?

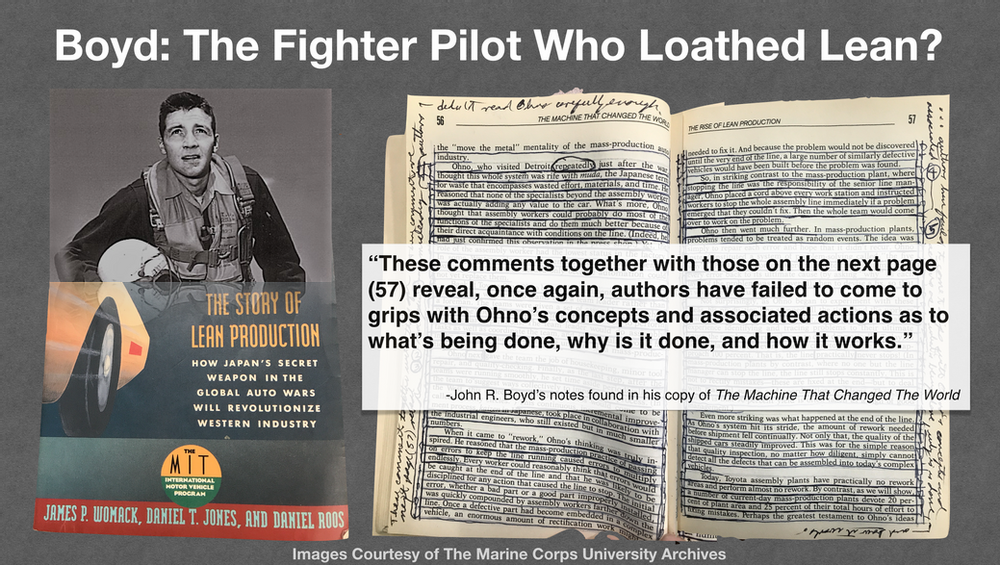

As a retired pilot who liked to read, John Boyd studied the Toyota Production System and embraced the teachings of Taiichi Ohno and Shigeo Shingo. He also read many early “Lean” thinking books and marked them up, a lot, and often commented in the margins on the author’s familiarity (or lack thereof) with Ohno and Shingo:

“The authors failed to come to grips with Ohno’s concepts.”

“Authors did not read Ohno carefully enough.”

These comments and other like it found in the margins of John Boyd’s books and papers housed in The Marine Corps University Archives suggest he was not impressed with the interpretation of the Toyota Production System by early Lean thinkers. For example, in Boyd’s personal copy of The Machine that Changed the World, Boyd made this comment on the topics of flow and Kanban:

“Misleading explanation: First of all, Kanban is only part of the JIT system. Next, the authors don’t even come close to grips as to how it really works. Third, the way they laid out this chapter suggests they don’t really understand Ohno or they have a mindset that precludes them from doing so. In particular, they have not captured Ohno’s “reverse” thinking, the power of his ability to reach outside and combine it with his internal thinking.”

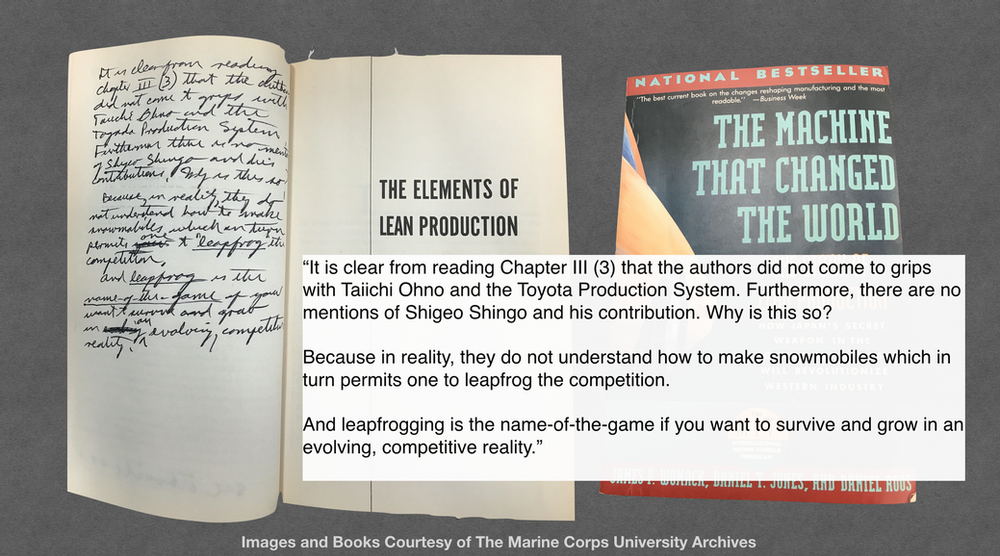

Here are his notes at the end of Chapter 3, The Machine that Changed the World:

The people who are often credited with coining the term “lean thinking” from their interpretation of the Toyota Production System, James P. Womack and Daniel T. Jones, are two of the three authors of The Machine That Changed the World. To Boyd, at least from his comments found in his copy of the book, these authors did not understand the Toyota Production System. Worse, they used a closed system metaphor to explain it (my opinion).

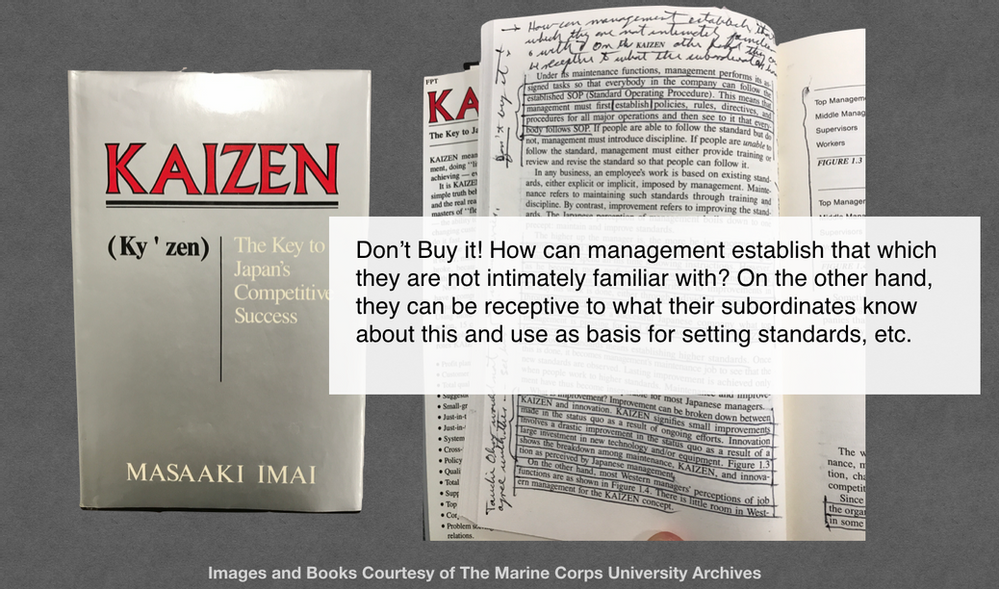

In Boyd’s copy of Masaaki Imai’s Kaizen: The Key to Japan’s Competitive Success, Boyd wrote this in the margins of page 27:

“This is not necessarily so (see Taiichi Ohno’s innovations that were people oriented).”

The above comment by Boyd was in response to this view by Masaaki Imai on Kaizen and innovation.

Investing in KAIZEN means investing in people. In Short, KAIZEN is people-oriented, whereas innovation is technology- and money-oriented.

Complexity-Based Safety and Human and Organizational Performance professionals should be interested in these comments (pictured) Boyd made on the role of management in establishing polices, rules, directives, and procedures.

From Imai’s Kaizen:

This means that management must first establish policies, rules, directives, and procedures for all major operations and then see to it that everybody follows SOP.

Boyd’s response (picture):

On the same page, Boyd pens, “Taiichi Ohno would not agree with this” in response to Imai’s view of improvement:

What is improvement? Improvement can be broken down between Kaizen and innovation. Kaizen signifies small improvements made in the status quo as a result of ongoing efforts. Innovation large investments in new technology and/or equipment.

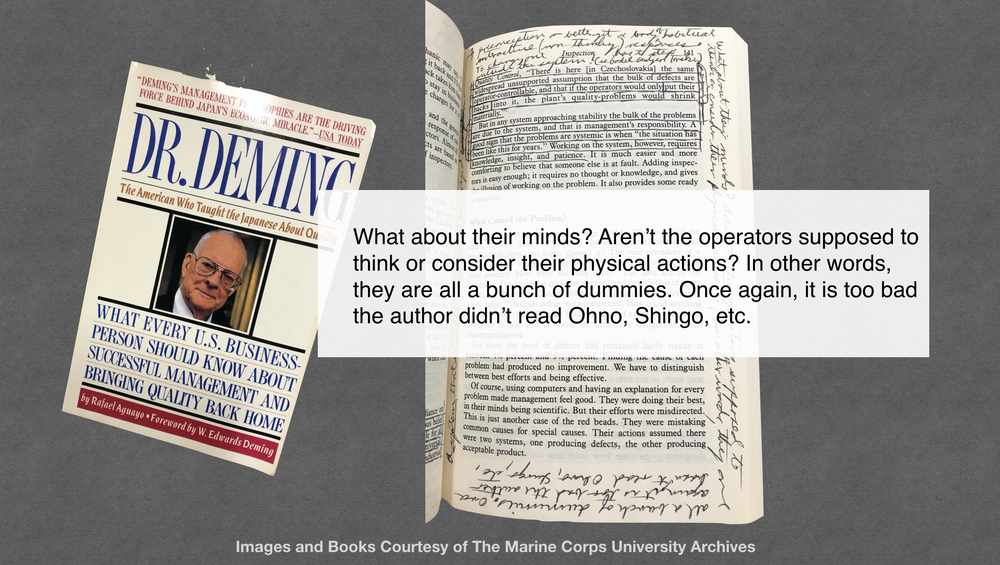

Bonus: Take a look Boyd’s note found on page 141 in Dr. Deming: The American Who Taught the Japanese About Quality:

“Once again, it is too bad the author didn’t read Ohno, Shingo, etc.”

A Gap Between TPS and Lean

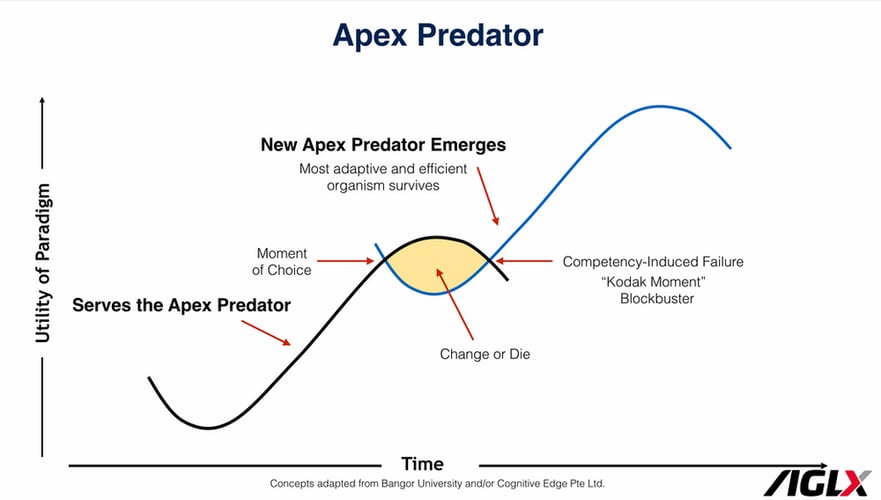

Boyd recognized a gap between the Toyota Production System and early Lean thinking. To Boyd, The Toyota Production System is a manifestation of maneuver warfare applied to a production system and shares the same principles he associated with Blitzkrieg, Sun Tzu, Musashi’s Book of Five Rings, and Cleary’s The Japanese Art of War [2]. But early Lean thinkers—those who put their Western bias on the Toyota Production System with the philosophy they labeled as Lean—did not share a similar orientation that Boyd developed not only through his studies of Japanese culture, but through his broad knowledge of science, strategy, and warfare.

Perhaps, as a result of his orientation, Boyd recognized the early need for Lean to evolve beyond the West’s mutated view of the Toyota Production System and why Boyd may have loathed Lean.

The Flow of Command and Control

At a later time, I will share some of Boyd’s thoughts on the Flow of Command and Control found in the margins of his copies of other TPS, Lean, and Quality books. From these findings, it is possible that the OODA loop is best viewed as a Knowledge or Information Flow System to be optimized to changing environments (think domains of Cynefin).

To learn more about the OODA loop, Lean, Flow, Kaizen, Cynefin, and more, take a look at The Flow Guide™.

Notes:

1. High-performing organizations, as the author of The Creator’s Code, Amy Wilkinson, puts it, “Fly the OODA loop.”

2. Richards, C. (2004). Certain to Win: The Strategy of John Boyd Applied to Business. Kindle edition.